Without a doubt, Spain’s rich history and the constant struggle for power are told beautifully through the eyes of its most talented authors. Literature has played a vital role in capturing its struggles, since hundreds of years before the infamous Civil War, to contemporary times. A great way to immerse yourself in the language and fully understand the struggles, victories, and themes of the Spanish culture throughout history is to experience it through the eyes of its beloved literary geniuses.

Miguel de Cervantes

September 29, 1547- April 22, 1616

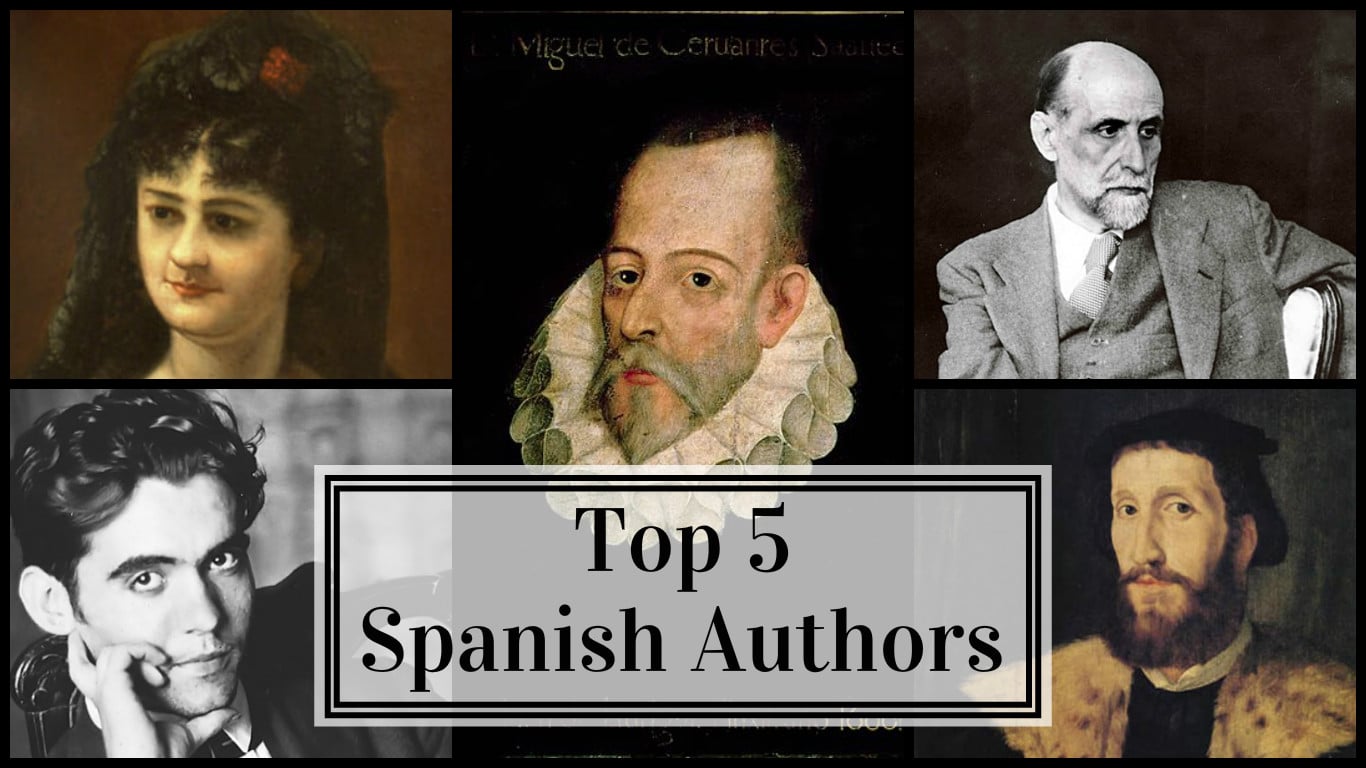

Federico García Lorca

June 5, 1898- August 19, 1936

Juan Ramón Jiménez

24 December 1881 – 29 May 1958

Emilia Pardo Bazán

September 16, 1851- May 12, 1921

Lazarillo de Tormes

1554

1 Comment. Leave new

Este Lazarillo de Tormes -: algo muy parecido a Alfonso de Valdés, el conocído humísta español, no?